Thanks to Adam Tarnter and the Fusion team, BikeIsBest is one of the very few newsletters I I make time to read — no matter how time-poor I am as a founder. It’s simply too important to miss. And today, it pointed me to a report I believe every transport policymaker should read.

The Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) has just published a crucial new study: “The Transport Challenge for Low-Income Households.”

At Mosa, we’ve long believed that the booming world of bicycle sharing doesn’t really serve those who need affordable transport the most. This report doesn’t just confirm our hunch — it adds depth, data, and urgency to it.

🚘 Car Dependency Is a Financial Trap

The report confirms what many of us might expect — that car ownership is financially ruinous for low-income families.

📊 Households in the lowest income quintile who own a car spend £76 a week on transport — equivalent to over a quarter of their income.(Source: IPPR, 2025)

That’s a staggering amount for someone just trying to get to work, drop their children at school, or care for a family member. It’s also a stark reminder: when no good alternatives exist, people pay for mobility with money they don’t have.

🚲 Cycling Is the Cheapest Mode — But Not the Most Accessible

We often hear that cycling is the ultimate affordable and sustainable mode of transport. The report supports this — walking and cycling come with minimal running costs. But affordability alone isn’t enough.

📊 Only 25% of individuals in households earning £14,999 or less per year have access to a bicycle — compared with 50% of people in households earning over £50,000.(DfT, 2024b via IPPR)

Why? The upfront costs of a bicycle, a lock, helmet, and safe gear can be enough to put it out of reach. On top of that, there’s often no safe infrastructure in place — no protected cycle lanes, no secure storage, no maintenance support.

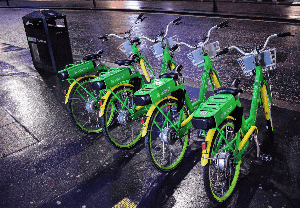

🚲💸 So Why Not Bike Sharing?

If the upfront cost of buying a bike — not to mention the constant risk of theft — makes ownership unrealistic for low-income households, then surely

bike sharing is the answer?

That’s the theory. Shared bikes are supposed to fill the gaps in public transport — the “first and last mile” solution. A flexible, low-cost option for those who don’t drive.

But here’s where it gets ironic.

In reality, bike sharing schemes are concentrated in wealthy city centres , places like central London or inner Manchester, where public transport is already abundant. The very areas that need them the least.

⛔️ Suburban and rural areas — where many vulnerable and low-income communities live — are often completely left out.

🚲 And the cost? In London, a 10-minute ride on Lime will set you back around £3.70. That’s not affordable daily transport for a person struggling to buy groceries — it’s a premium service for those with disposable income.

🔄 Reimagining Cycle Sharing for Real Impact

That’s why we’re rethinking cycle sharing at Mosa.

The traditional, top-down approach — whether it’s city-run schemes like Santander Cycles or profit-driven operators like Lime and Voi — just doesn’t work outside central urban areas. And certainly not for the communities that actually needaffordable, accessible transport the most.

Could a community-owned, community-led model work better? Could a funding model that draws on community buy-in, rather than relying solely on local authority grants, be more sustainable?

We don’t have all the answers yet. There’s still more to test, learn, and prove.

But we’re energised by the opportunity to build something that directly addresses the gaps laid bare in this report — a cycle sharing model that puts accessibility and inclusion first.