Dockless Is Winning the Market

Dockless bike sharing is rapidly outpacing traditional docked systems. In 2023, dockless models captured nearly 60 % of global market share, up from roughly 45 % in 2020 . The global bike-sharing market, valued at ~USD 9 billion in 2024, is projected to grow at ~7–11 % annually, with dockless systems leading in expansion .

A key reason for this dominance is cost. Docked systems require significant capital investment in fixed infrastructure—stations, land use, planning permissions, and ongoing maintenance. As a result, only well-resourced and committed cities can afford to sustain them. Dockless systems, by contrast, demand minimal upfront infrastructure and can be deployed flexibly, often with little more than municipal permission and GPS-enabled bikes.

But it’s not just about cost—user preference also plays a decisive role. Riders are drawn to the convenience of dockless systems: pick up a bike anywhere, and drop it off anywhere. This flexibility makes dockless options far more appealing for spontaneous or short trips.

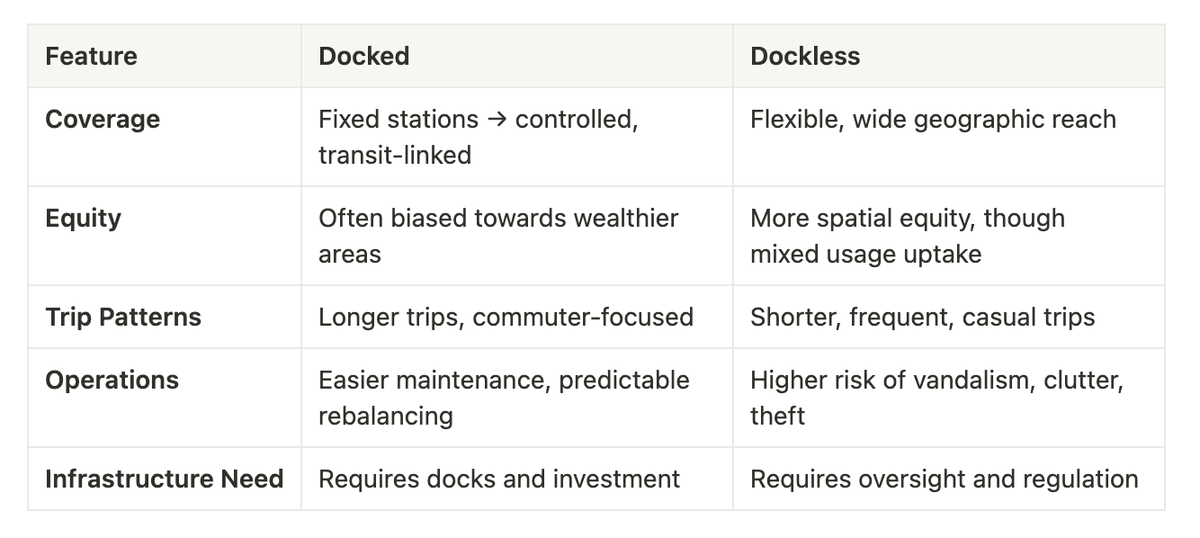

Docked vs Dockless: Two Models, Two Worlds

Docked and dockless systems reflect fundamentally different design philosophies, operational models, and public expectations.

While GPS and mobile tech have improved the ability to track and prompt proper usage (e.g. through app alerts, digital incentives, and parking guidelines), the reality is less tidy. Even if just a small fraction of bikes are mis-parked, the absolute number is enough to generate visible disorder, especially in dense urban areas. Cities from Paris to San Francisco have grappled with cluttered pavements, blocked pedestrian routes, and public frustration—even in systems designed to “self-regulate.”

Studies have shown that dockless bikes tend to cluster in wealthier, high-traffic zones, unless strong equity-focused policies are in place. Meanwhile, docked systems, despite offering predictability, often lack the geographic reach needed to serve lower-income or peripheral communities

Why Private Operators Prefer Dockless

The majority of private micromobility operators—such as Lime, Dott, Tier, and Bird—have embraced the dockless model as their default operating strategy. For high-growth, venture-backed companies, it offers a business model that is low in capital intensity, fast to deploy, and easy to scale.

Once granted a permit—often lasting just 1–3 years—operators can quickly flood an area with bikes, begin collecting usage data, and generate revenue. If uptake is strong, they can scale up fleets with minimal friction. If performance lags or regulations tighten, they can just as easily scale down, pause service, or exit the market altogether. This flexibility is essential for startups managing variable regulation, tight unit economics, and investor growth expectations.

Cities, too, often view dockless systems as a “low-commitment” solution. With no fixed infrastructure to approve or maintain, a permit-based system allows cities to pilot services with less political or financial risk. If an operator underperforms—or causes problems with clutter or maintenance—municipalities can revoke the permit and require the company to collect its vehicles. This illusion of reversibility makes dockless schemes politically easier to authorise than investing public funds in docks, land use, and long-term contracts. Paris, Madrid, and Melbourne have all suspended or severely limited dockless e-scooter services due to clutter, enforcement issues, or permit misuse

But while this flexibility benefits both cities and operators in the short term, it also exposes structural weaknesses. The temporary nature of the permits means private companies are less incentivised to invest in long-term service equity, reliability, or integration with public transport goals.

The Hidden Costs of Free‑Floating Dockless

Dockless bike sharing offers speed, flexibility, and low upfront costs—but those advantages can obscure a series of significant public costs. Over time, these externalities add up—eroding public trust and demanding intervention from city authorities.

🚧 Clutter and Public Space Disruption

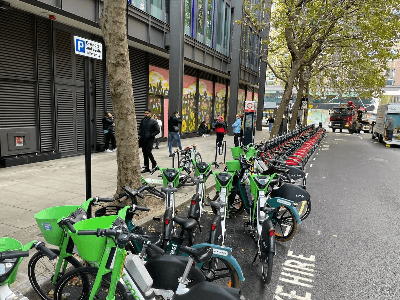

One of the most visible and persistent downsides of dockless systems is urban clutter. Without physical docks to anchor fleet behaviour, bikes (and increasingly e-bikes) often end up obstructing pavements, green spaces, and transit areas.

While GPS and geofencing tools have improved, they often act more like guidelines than enforcement mechanisms. The result? A small percentage of misbehaving users still generate large-scale disruption in public space.

🛠️ Vandalism, Theft, and Maintenance Burden

Dockless bikes, lacking physical locking stations, are more vulnerable to damage, misuse, and loss—especially in unmonitored or low-traffic areas.

- Mobike withdrew from Manchester in 2018 due to what it called “unsustainable levels” of theft and vandalism. The same fate befell early operators in Newcastle and Cambridge.

- In Lisbon, Bikeshare Lisbon lost over 189 e-bikes in three months, including many dumped into the Tagus river.

- Although these incidents date back to 2017–2018, their legacy shapes current policies. Recent operator suspensions in San Francisco (2022) and increased scrutiny in Paris (2023) over micromobility disorder show that vandalism and regulation remain ongoing concerns.

Operators have since introduced stronger bike hardware and better tracking—but city agencies still report recurring losses and dumping, especially when services expand too quickly or enter areas without dedicated support.

🧹The Cleanup Burden Falls on Cities

Cities often end up bearing the logistical and financial cost of cleaning up after dockless systems. When bikes are damaged, abandoned, or parked illegally, it’s municipal workers—not operators—who are called to intervene.

Even as cities like London impose fines or restrict parking zones, they still fund public infrastructure to mitigate problems—undermining the original narrative that dockless systems are “free” for municipalities. The true cost of convenience, in many cases, is passed to the public sector.

Is Geo‑Fencing Really the Answer?

Ask any operator how they plan to solve the problem of cluttered pavements and abandoned bikes, and they’ll likely point to geo-fencing—digital “drop zones” enforced by GPS and in-app controls. In cities like London, these zones are now marked with painted bays or signage, and some operators claim to use sensors to detect whether a bike is parked correctly within them.

But is it that simple?

🚲 The Reality: Geo‑Fencing Has Limits

Despite technological improvements, geo-fencing is far from a reliable solution—especially when used in place of physical infrastructure or enforcement:

- GPS inaccuracies are common in dense urban environments with tall buildings (“urban canyons”). In central London or Manhattan, a bike may register as compliant while sitting metres outside the actual zone.

- User enforcement is minimal. While apps may send alerts or deny trip completion if a bike is mis-parked, these penalties are often weak, inconsistent, or easy to bypass. Few operators levy meaningful fines or suspensions for non-compliance.

- Behaviour change remains elusive. Even where designated bays exist, many users still park vehicles outside them—often for convenience or lack of awareness. In London, despite extensive geo-fencing efforts, bikes continue to obstruct pavements, prompting boroughs to seize and impound them.

📱Tech Can Help—But It’s Not Enough

Geo-fencing is a tool—not a solution. Without physical parking infrastructure, consistent city-led enforcement, and better rider education, the system will continue to fall short.

In truth, relying solely on digital boundaries gives a false sense of order. The bikes are still there. The clutter is still there. And the public costs are still there.

Is geo-fencing is not the only answer. Is private operator domained dockless model just cannot address the need and accessibility to the mass.

What are the alternatives? Are people working or discussing the alternatives? We will explore those issue in Part 2.

⛔ A Flawed Model for Mass Accessibility?

Geo-fencing may help control disorder—but it doesn’t solve the structural limitations of the dockless model itself. Private, operator-led systems are designed around profitability and speed of deployment—not long-term public accessibility or spatial equity.

If shared cycling is to serve everyone, not just high-demand areas, the model needs to evolve. Perhaps it’s time to ask:

- Are there better alternatives?

- What role should cities play in shaping these systems?

- Can docked models return in more affordable, scalable forms?

We’ll explore those questions—and the future of city-led shared mobility—in Part 2.